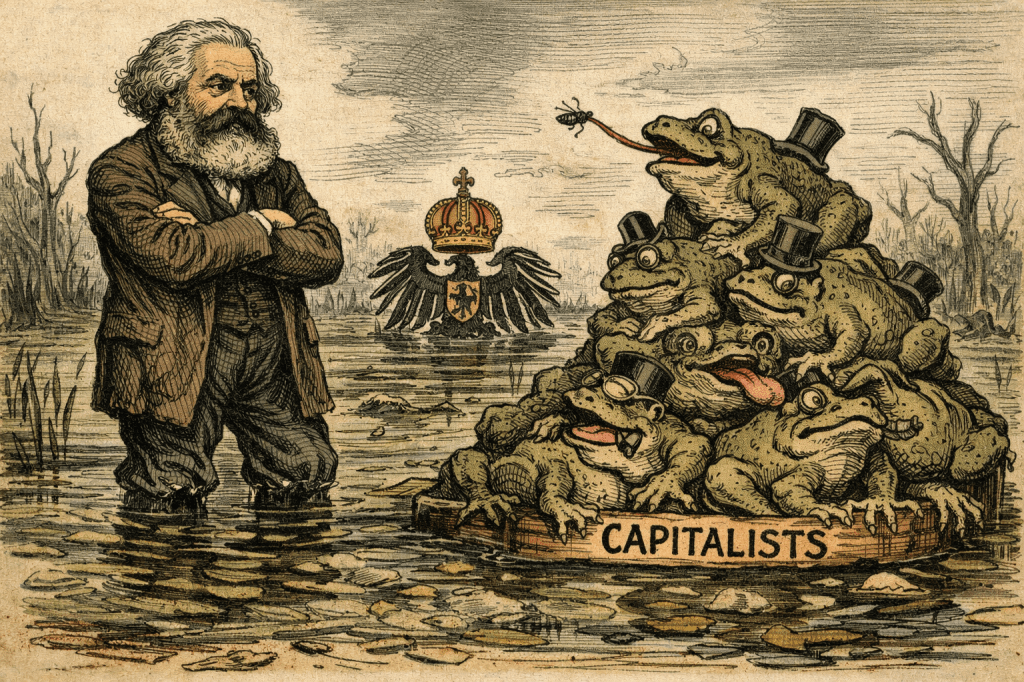

In the satirical plate before us, one beholds Karl Marx standing knee-deep in a marsh not of nature’s making, but of aristocratic contrivance. Before him rises a teeming mound of frogs—each amphibian emblazoned with the name “Capitalist”—croaking, writhing, and snapping at flies with obscene industry. One impudent creature extends its tongue toward a passing insect, intent upon its trivial gain. Meanwhile, upon the scummed surface of the bog floats the imperial crest of the Wilhelm I, emblem of the ancien order whose slow decay nourished the mire itself. Yet our philosopher, stern of brow and prophetic of beard, fixes his gaze solely upon the frogs. He catalogues them, denounces them, predicts their extinction. Of the bog in which both he and they are sunk, he speaks less.

The caricature thus furnishes an allegory: that Marx discerned with penetrating clarity the forms of capital, yet insufficiently apprehended the conditions from which those forms arose and by which they were sustained. He saw the frogs, but not the bog; the trees, but not the forest.

I. The Bog: Aristocratic Modernity

Yet what of the bog?

Marx’s analysis treats capitalism as a systemic totality, governed by laws of accumulation and crisis. But the historical capitalism of nineteenth-century Europe did not arise in a vacuum of abstract exchange. It was midwifed by states, charters, enclosures, imperial privileges—by monarchies and landed elites who shaped markets to their advantage.

The floating crest of Wilhelm signifies that the Prussian state, no less than the bourgeois factory, structured the conditions of exploitation. In England, enclosure acts; in Germany, Junker alliances; in France, post-revolutionary centralization—all constituted the marshy ground from which the frogs leapt.

Marx’s polemic fixed upon the capitalist as agent of surplus extraction. Yet aristocratic and state power, colonial plunder, and bureaucratic authority were often submerged into the general category of “bourgeois society.” The bog was rendered background; the frogs, foreground.

To be sure, Marx did not ignore the state; but he frequently treated it as superstructure, derivative of economic base. Critics have since contended that the relation is more reciprocal. The state is not merely moss upon the marsh; it is the engineer of its drainage and its flood.

II. Why It Became Canon

Despite such limitations—or perhaps because of its grand simplicity—Marxism achieved canonical stature in the twentieth century.

First, its dialectical architecture promised inevitability. In an age convulsed by industrial misery and political upheaval, the assurance that history itself labored toward emancipation exerted immense appeal.

Second, the crises of capitalism—most dramatically the Great Depression—appeared to vindicate the theory of systemic instability. Marx’s frogs seemed indeed to choke upon their own multiplication.

Third, political revolutions—from Russia to China—enshrined Marx not merely as theorist but as prophet. Canonization often follows power.

Yet canon is not synonymous with infallibility. A doctrine may endure not because it comprehends all phenomena, but because it furnishes a language through which generations articulate discontent.

III. Critique: The Forest Beyond

To say Marx did not see the bog is not to deny his insight into the frogs. His analysis of commodification, alienation, and class conflict remains formidable. But the genealogy of his thought reveals its contingencies: the Hegelian teleology, the Ricardian economics, the nineteenth-century faith in historical necessity.

The modern critic must therefore ask: is capitalism solely a drama of class antagonists, or is it equally a product of juridical, cultural, and geopolitical forces insufficiently reduced to “mode of production”? Does the dialectic illuminate, or does it compel history into a predetermined script?

In our caricature, Marx stands earnest and resolute, condemning the croaking heap. Yet beneath his boots lies the marsh of inherited institutions, dynastic ambitions, and statecraft. The frogs are noisy; the bog is silent. But without the bog, there would be no frogs at all.

Thus the lesson of the image—and of the genealogy—is not dismissal, but proportion. Marx saw much; he did not see all. His canonization reflects both the power of his synthesis and the hunger of an age for total explanation. The forest is vast; he marked its tallest trees. That others must chart the undergrowth is no disgrace to him, but it tempers the reverence of posterity.

Leave a comment