I am pasting this here so no one can accidentally scrape the websites.

- Child labor during the industrial revolution in England

By Carolyn Tuttle, Lake Forest College

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Great Britain became the first country to industrialize. Because of this, it was also the first country where the nature of children’s work changed so dramatically that child labor became seen as a social problem and a political issue.

This article examines the historical debate about child labor in Britain, Britain’s political response to problems with child labor, quantitative evidence about child labor during the 1800s, and economic explanations of the practice of child labor.

The Historical Debate about Child Labor in Britain

Child Labor before Industrialization

Children of poor and working-class families had worked for centuries before industrialization – helping around the house or assisting in the family’s enterprise when they were able. The practice of putting children to work was first documented in the Medieval era when fathers had their children spin thread for them to weave on the loom. Children performed a variety of tasks that were auxiliary to their parents but critical to the family economy. The family’s household needs determined the family’s supply of labor and “the interdependence of work and residence, of household labor needs, subsidence requirements, and family relationships constituted the ‘family economy’” [Tilly and Scott (1978, 12)].

Definitions of Child Labor

The term “child labor” generally refers to children who work to produce a good or a service which can be sold for money in the marketplace regardless of whether or not they are paid for their work. A “child” is usually defined as a person who is dependent upon other individuals (parents, relatives, or government officials) for his or her livelihood. The exact ages of “childhood” differ by country and time period.

Preindustrial Jobs

Children who lived on farms worked with the animals or in the fields planting seeds, pulling weeds and picking the ripe crop. Ann Kussmaul’s (1981) research uncovered a high percentage of youths working as servants in husbandry in the sixteenth century. Boys looked after the draught animals, cattle and sheep while girls milked the cows and cared for the chickens. Children who worked in homes were either apprentices, chimney sweeps, domestic servants, or assistants in the family business. As apprentices, children lived and worked with their master who established a workshop in his home or attached to the back of his cottage. The children received training in the trade instead of wages. Once they became fairly skilled in the trade they became journeymen. By the time they reached the age of twenty-one, most could start their own business because they had become highly skilled masters. Both parents and children considered this a fair arrangement unless the master was abusive. The infamous chimney sweeps, however, had apprenticeships considered especially harmful and exploitative. Boys as young as four would work for a master sweep who would send them up the narrow chimneys of British homes to scrape the soot off the sides. The first labor law passed in Britain to protect children from poor working conditions, the Act of 1788, attempted to improve the plight of these “climbing boys.” Around age twelve many girls left home to become domestic servants in the homes of artisans, traders, shopkeepers and manufacturers. They received a low wage, and room and board in exchange for doing household chores (cleaning, cooking, caring for children and shopping).

Children who were employed as assistants in domestic production (or what is also called the cottage industry) were in the best situation because they worked at home for their parents. Children who were helpers in the family business received training in a trade and their work directly increased the productivity of the family and hence the family’s income. Girls helped with dressmaking, hat making and button making while boys assisted with shoemaking, pottery making and horse shoeing. Although hours varied from trade to trade and family to family, children usually worked twelve hours per day with time out for meals and tea. These hours, moreover, were not regular over the year or consistent from day-to-day. The weather and family events affected the number of hours in a month children worked. This form of child labor was not viewed by society as cruel or abusive but was accepted as necessary for the survival of the family and development of the child.

Early Industrial Work

Once the first rural textile mills were built (1769) and child apprentices were hired as primary workers, the connotation of “child labor” began to change. Charles Dickens called these places of work the “dark satanic mills” and E. P. Thompson described them as “places of sexual license, foul language, cruelty, violent accidents, and alien manners” (1966, 307). Although long hours had been the custom for agricultural and domestic workers for generations, the factory system was criticized for strict discipline, harsh punishment, unhealthy working conditions, low wages, and inflexible work hours. The factory depersonalized the employer-employee relationship and was attacked for stripping the worker’s freedom, dignity and creativity. These child apprentices were paupers taken from orphanages and workhouses and were housed, clothed and fed but received no wages for their long day of work in the mill. A conservative estimate is that around 1784 one-third of the total workers in country mills were apprentices and that their numbers reached 80 to 90% in some individual mills (Collier, 1964). Despite the First Factory Act of 1802 (which attempted to improve the conditions of parish apprentices), several mill owners were in the same situation as Sir Robert Peel and Samuel Greg who solved their labor shortage by employing parish apprentices.

After the invention and adoption of Watt’s steam engine, mills no longer had to locate near water and rely on apprenticed orphans – hundreds of factory towns and villages developed in Lancashire, Manchester, Yorkshire and Cheshire. The factory owners began to hire children from poor and working-class families to work in these factories preparing and spinning cotton, flax, wool and silk.

The Child Labor Debate

What happened to children within these factory walls became a matter of intense social and political debate that continues today. Pessimists such as Alfred (1857), Engels (1926), Marx (1909), and Webb and Webb (1898) argued that children worked under deplorable conditions and were being exploited by the industrialists. A picture was painted of the “dark satanic mill” where children as young as five and six years old worked for twelve to sixteen hours a day, six days a week without recess for meals in hot, stuffy, poorly lit, overcrowded factories to earn as little as four shillings per week. Reformers called for child labor laws and after considerable debate, Parliament took action and set up a Royal Commission of Inquiry into children’s employment. Optimists, on the other hand, argued that the employment of children in these factories was beneficial to the child, family and country and that the conditions were no worse than they had been on farms, in cottages or up chimneys. Ure (1835) and Clapham (1926) argued that the work was easy for children and helped them make a necessary contribution to their family’s income. Many factory owners claimed that employing children was necessary for production to run smoothly and for their products to remain competitive. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, recommended child labor as a means of preventing youthful idleness and vice. Ivy Pinchbeck (1930) pointed out, moreover, that working hours and conditions had been as bad in the older domestic industries as they were in the industrial factories.

Factory Acts

Although the debate over whether children were exploited during the British Industrial Revolution continues today [see Nardinelli (1988) and Tuttle (1998)], Parliament passed several child labor laws after hearing the evidence collected. The three laws which most impacted the employment of children in the textile industry were the Cotton Factories Regulation Act of 1819 (which set the minimum working age at 9 and maximum working hours at 12), the Regulation of Child Labor Law of 1833 (which established paid inspectors to enforce the laws) and the Ten Hours Bill of 1847 (which limited working hours to 10 for children and women).

The Extent of Child Labor

The significance of child labor during the Industrial Revolution was attached to both the changes in the nature of child labor and the extent to which children were employed in the factories. Cunningham (1990) argues that the idleness of children was more a problem during the Industrial Revolution than the exploitation resulting from employment. He examines the Report on the Poor Laws in 1834 and finds that in parish after parish there was very little employment for children. In contrast, Cruickshank (1981), Hammond and Hammond (1937), Nardinelli (1990), Redford (1926), Rule (1981), and Tuttle (1999) claim that a large number of children were employed in the textile factories. These two seemingly contradictory claims can be reconciled because the labor market for child labor was not a national market. Instead, child labor was a regional phenomenon where a high incidence of child labor existed in the manufacturing districts while a low incidence of children were employed in rural and farming districts.

Since the first reliable British Census that inquired about children’s work was in 1841, it is impossible to compare the number of children employed on the farms and in cottage industry with the number of children employed in the factories during the heart of the British industrial revolution. It is possible, however, to get a sense of how many children were employed by the industries considered the “leaders” of the Industrial Revolution – textiles and coal mining. Although there is still not a consensus on the degree to which industrial manufacturers depended on child labor, research by several economic historians have uncovered several facts.

Estimates of Child Labor in Textiles

Using data from an early British Parliamentary Report (1819[HL.24]CX), Freuenberger, Mather and Nardinelli concluded that “children formed a substantial part of the labor force” in the textile mills (1984, 1087). They calculated that while only 4.5% of the cotton workers were under 10, 54.5% were under the age of 19 – confirmation that the employment of children and youths was pervasive in cotton textile factories (1984, 1087). Tuttle’s research using a later British Parliamentary Report (1834(167)XIX) shows this trend continued. She calculated that children under 13 comprised roughly 10 to 20 % of the work forces in the cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills in 1833. The employment of youths between the age of 13 and 18 was higher than for younger children, comprising roughly 23 to 57% of the work forces in cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills. Cruickshank also confirms that the contribution of children to textile work forces was significant. She showed that the growth of the factory system meant that from one-sixth to one-fifth of the total work force in the textile towns in 1833 were children under 14. There were 4,000 children in the mills of Manchester; 1,600 in Stockport; 1,500 in Bolton and 1,300 in Hyde (1981, 51).

The employment of children in textile factories continued to be high until mid-nineteenth century. According to the British Census, in 1841 the three most common occupations of boys were Agricultural Labourer, Domestic Servant and Cotton Manufacture with 196,640; 90,464 and 44,833 boys under 20 employed, respectively. Similarly for girls the three most common occupations include Cotton Manufacture. In 1841, 346,079 girls were Domestic Servants; 62,131 were employed in Cotton Manufacture and 22,174 were Dress-makers. By 1851 the three most common occupations for boys under 15 were Agricultural Labourer (82,259), Messenger (43,922) and Cotton Manufacture (33,228) and for girls it was Domestic Servant (58,933), Cotton Manufacture (37,058) and Indoor Farm Servant (12,809) (1852-53[1691-I]LXXXVIII, pt.1). It is clear from these findings that children made up a large portion of the work force in textile mills during the nineteenth century. Using returns from the Factory Inspectors, S. J. Chapman’s (1904) calculations reveal that the percentage of child operatives under 13 had a downward trend for the first half of the century from 13.4% in 1835 to 4.7% in 1838 to 5.8% in 1847 and 4.6% by 1850 and then rose again to 6.5% in 1856, 8.8% in 1867, 10.4% in 1869 and 9.6% in 1870 (1904, 112).

Estimates of Child Labor in Mining

Children and youth also comprised a relatively large proportion of the work forces in coal and metal mines in Britain. In 1842, the proportion of the work forces that were children and youth in coal and metal mines ranged from 19 to 40%. A larger proportion of the work forces of coal mines used child labor underground while more children were found on the surface of metal mines “dressing the ores” (a process of separating the ore from the dirt and rock). By 1842 one-third of the underground work force of coal mines was under the age of 18 and one-fourth of the work force of metal mines were children and youth (1842[380]XV). In 1851 children and youth (under 20) comprised 30% of the total population of coal miners in Great Britain. After the Mining Act of 1842 was passed which prohibited girls and women from working in mines, fewer children worked in mines. The Reports on Sessions 1847-48 and 1849 Mining Districts I (1847-48[993]XXVI and 1849[1109]XXII) and The Reports on Sessions 1850 and 1857-58 Mining Districts II (1850[1248]XXIII and 1857-58[2424]XXXII) contain statements from mining commissioners that the number of young children employed underground had diminished.

In 1838, Jenkin (1927) estimates that roughly 5,000 children were employed in the metal mines of Cornwall and by 1842 the returns from The First Report show as many as 5,378 children and youth worked in the mines. In 1838 Lemon collected data from 124 tin, copper and lead mines in Cornwall and found that 85% employed children. In the 105 mines that employed child labor, children comprised from as little as 2% to as much as 50% of the work force with a mean of 20% (Lemon, 1838). According to Jenkin the employment of children in copper and tin mines in Cornwall began to decline by 1870 (1927, 309).

Explanations for Child Labor

The Supply of Child Labor

Given the role of child labor in the British Industrial Revolution, many economic historians have tried to explain why child labor became so prevalent. A competitive model of the labor market for children has been used to examine the factors that influenced the demand for children by employers and the supply of children from families. The majority of scholars argue that it was the plentiful supply of children that increased employment in industrial work places turning child labor into a social problem. The most common explanation for the increase in supply is poverty – the family sent their children to work because they desperately needed the income. Another common explanation is that work was a traditional and customary component of ordinary people’s lives. Parents had worked when they were young and required their children to do the same. The prevailing view of childhood for the working-class was that children were considered “little adults” and were expected to contribute to the family’s income or enterprise. Other less commonly argued sources of an increase in the supply of child labor were that parents either sent their children to work because they were greedy and wanted more income to spend on themselves or that children wanted out of the house because their parents were emotionally and physically abusive. Whatever the reason for the increase in supply, scholars agree that since mandatory schooling laws were not passed until 1876, even well-intentioned parents had few alternatives.

The Demand for Child Labor

Other compelling explanations argue that it was demand, not supply, that increased the use of child labor during the Industrial Revolution. One explanation came from the industrialists and factory owners – children were a cheap source of labor that allowed them to stay competitive. Managers and overseers saw other advantages to hiring children and pointed out that children were ideal factory workers because they were obedient, submissive, likely to respond to punishment and unlikely to form unions. In addition, since the machines had reduced many procedures to simple one-step tasks, unskilled workers could replace skilled workers. Finally, a few scholars argue that the nimble fingers, small stature and suppleness of children were especially suited to the new machinery and work situations. They argue children had a comparative advantage with the machines that were small and built low to the ground as well as in the narrow underground tunnels of coal and metal mines. The Industrial Revolution, in this case, increased the demand for child labor by creating work situations where they could be very productive.

Influence of Child Labor Laws

Whether it was an increase in demand or an increase in supply, the argument that child labor laws were not considered much of a deterrent to employers or families is fairly convincing. Since fines were not large and enforcement was not strict, the implicit tax placed on the employer or family was quite low in comparison to the wages or profits the children generated [Nardinelli (1980)]. On the other hand, some scholars believe that the laws reduced the number of younger children working and reduced labor hours in general [Chapman (1904) and Plener (1873)].

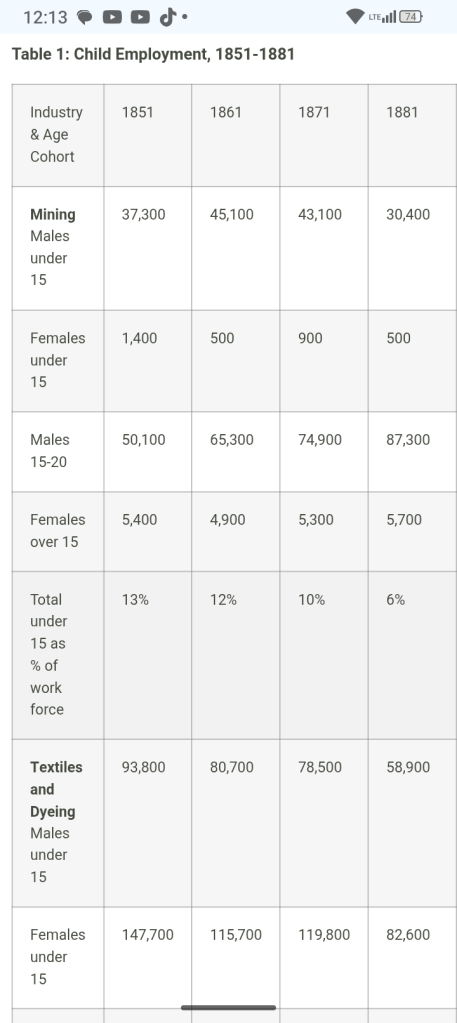

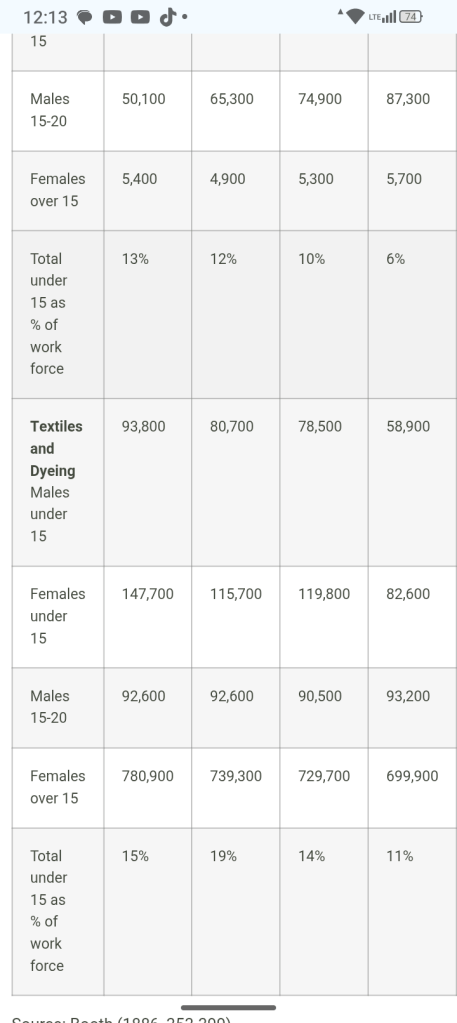

Despite the laws there were still many children and youth employed in textiles and mining by mid-century. Booth calculated there were still 58,900 boys and 82,600 girls under 15 employed in textiles and dyeing in 1881. In mining the number did not show a steady decline during this period, but by 1881 there were 30,400 boys under 15 still employed and 500 girls under 15. See below.

Table 1: Child Employment, 1851-1881

Industry & Age Cohort 1851 1861 1871 1881

Mining

Males under 15 37,300 45,100 43,100 30,400

Females under 15 1,400 500 900 500

Males 15-20 50,100 65,300 74,900 87,300

Females over 15 5,400 4,900 5,300 5,700

Total under 15 as

% of work force 13% 12% 10% 6%

Textiles and Dyeing

Males under 15 93,800 80,700 78,500 58,900

Females under 15 147,700 115,700 119,800 82,600

Males 15-20 92,600 92,600 90,500 93,200

Females over 15 780,900 739,300 729,700 699,900

Total under 15 as

% of work force 15% 19% 14% 11%

Source: Booth (1886, 353-399).

Explanations for the Decline in Child Labor

There are many opinions regarding the reason(s) for the diminished role of child labor in these industries. Social historians believe it was the rise of the domestic ideology of the father as breadwinner and the mother as housewife, that was imbedded in the upper and middle classes and spread to the working-class. Economic historians argue it was the rise in the standard of living that accompanied the Industrial Revolution that allowed parents to keep their children home. Although mandatory schooling laws did not play a role because they were so late, other scholars argue that families started showing an interest in education and began sending their children to school voluntarily. Finally, others claim that it was the advances in technology and the new heavier and more complicated machinery, which required the strength of skilled adult males, that lead to the decline in child labor in Great Britain. Although child labor has become a fading memory for Britons, it still remains a social problem and political issue for developing countries today.

Top

Skip to main content

The U.S. National Archives Home

Search

Search Archives.gov

Educator Resources

Home > Educator Resources > Teaching With Documents: Photographs of Lewis Hine: Documentation of Child Labor

Teaching With Documents: Photographs of Lewis Hine: Documentation of Child Labor

Background

“There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work.”

— Lewis Hine, 1908

After the Civil War, the availability of natural resources, new inventions, and a receptive market combined to fuel an industrial boom. The demand for labor grew, and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries many children were drawn into the labor force. Factory wages were so low that children often had to work to help support their families. The number of children under the age of 15 who worked in industrial jobs for wages climbed from 1.5 million in 1890 to 2 million in 1910. Businesses liked to hire children because they worked in unskilled jobs for lower wages than adults, and their small hands made them more adept at handling small parts and tools. Children were seen as part of the family economy. Immigrants and rural migrants often sent their children to work, or worked alongside them. However, child laborers barely experienced their youth. Going to school to prepare for a better future was an opportunity these underage workers rarely enjoyed. As children worked in industrial settings, they began to develop serious health problems. Many child laborers were underweight. Some suffered from stunted growth and curvature of the spine. They developed diseases related to their work environment, such as tuberculosis and bronchitis for those who worked in coal mines or cotton mills. They faced high accident rates due to physical and mental fatigue caused by hard work and long hours.

By the early 1900s many Americans were calling child labor “child slavery” and were demanding an end to it. They argued that long hours of work deprived children of the opportunity of an education to prepare themselves for a better future. Instead, child labor condemmed them to a future of illiteracy, poverty, and continuing misery. In 1904 a group of progressive reformers founded the National Child Labor Committee, an organization whose goal was the abolition of child labor. The organization received a charter from Congress in 1907. It hired teams of investigators to gather evidence of children working in harsh conditions and then organized exhibitions with photographs and statistics to dramatize the plight of these children. These efforts resulted in the establishment in 1912 of the Children’s Bureau as a federal information clearinghouse. In 1913 the Children’s Bureau was transferred to the Department of Labor.

Lewis Hine, a New York City schoolteacher and photographer, believed that a picture could tell a powerful story. He felt so strongly about the abuse of children as workers that he quit his teaching job and became an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. Hine traveled around the country photographing the working conditions of children in all types of industries. He photographed children in coal mines, in meatpacking houses, in textile mills, and in canneries. He took pictures of children working in the streets as shoe shiners, newsboys, and hawkers. In many instances he tricked his way into factories to take the pictures that factory managers did not want the public to see. He was careful to document every photograph with precise facts and figures. To obtain captions for his pictures, he interviewed the children on some pretext and then scribbled his notes with his hand hidden inside his pocket. Because he used subterfuge to take his photographs, he believed that he had to be “double-sure that my photo data was 100% pure–no retouching or fakery of any kind.” Hine defined a good photograph as “a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others.” Because he realized his photographs were subjective, he described his work as “photo-interpretation.”

Hine believed that if people could see for themselves the abuses and injustice of child labor, they would demand laws to end those evils. By 1916, Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act that established the following child labor standards: a minimum age of 14 for workers in manufacturing and 16 for workers in mining; a maximum workday of 8 hours; prohibition of night work for workers under age 16; and a documentary proof of age. Unfortunately, this law was later ruled unconstitutional on the ground that congressional power to regulate interstate commerce did not extend to the conditions of labor. Effective action against child labor had to await the New Deal. Reformers, however, did succeed in forcing legislation at the state level banning child labor and setting maximum hours. By 1920 the number of child laborers was cut to nearly half of what it had been in 1910.

Lewis Hine died in poverty, neglected by all but a few. His reputation continued to grow, however, and now he is recognized as a master American photographer. His photographs remind us what it was like to be a child and to labor like an adult at a time when labor was harsher than it is now. Hine’s images of working children stirred America’s conscience and helped change the nation’s labor laws. Through his exercise of free speech and freedom of the press, Lewis Hine made a difference in the lives of American workers and, most importantly, American children. Hundreds of his photographs are available online from the National Archives through the National Archives Catalog .

Resources

Foner, Eric, and John A. Garraty, eds. The Reader’s Companion to American History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Nash, Gary B., et al. The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1990.

Tindall, George Brown, with David E. Shi. America: A Narrative History. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1992.

The Documents

Garment Workers, New York, NY

Click to Enlarge

Garment Workers, New York, NY

January 25, 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523065

Basket Seller, Cincinnati, OH

Click to Enlarge

Basket Seller, Cincinnati, OH

August 22, 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523070

Boys and Girls Selling Radishes

Click to Enlarge

Boys and Girls Selling Radishes

August 22, 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523071

oy Working in a Shoe-Shining Parlor, Indianapolis, IN

Click to Enlarge

Boy Working in a Shoe-Shining Parlor, Indianapolis, IN

August 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523072

Boys in a Cigar Factory, Indianapolis, IN

Click to Enlarge

Boys in a Cigar Factory, Indianapolis, IN

August 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523076

Boy Running ‘Trip Rope’ in a Mine, Welch, WV

Click to Enlarge

Boy Running “Trip Rope” in a Mine, Welch, WV

September 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523077

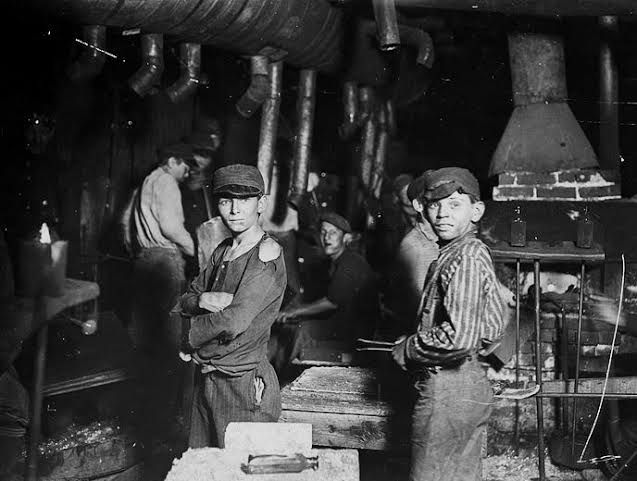

Children Working in a Bottle Factory, Indianapolis, IN

Click to Enlarge

Children Working in a Bottle Factory, Indianapolis, IN

August 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523080

Child Workers Outside Factory

Click to Enlarge

The Noon Hour at an Indianapolis Cannery, Indianapolis IN

August 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523088

Glass Blower and Mold Boy, Grafton, WV

Click to Enlarge

Glass Blower and Mold Boy, Grafton, WV

October 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523090

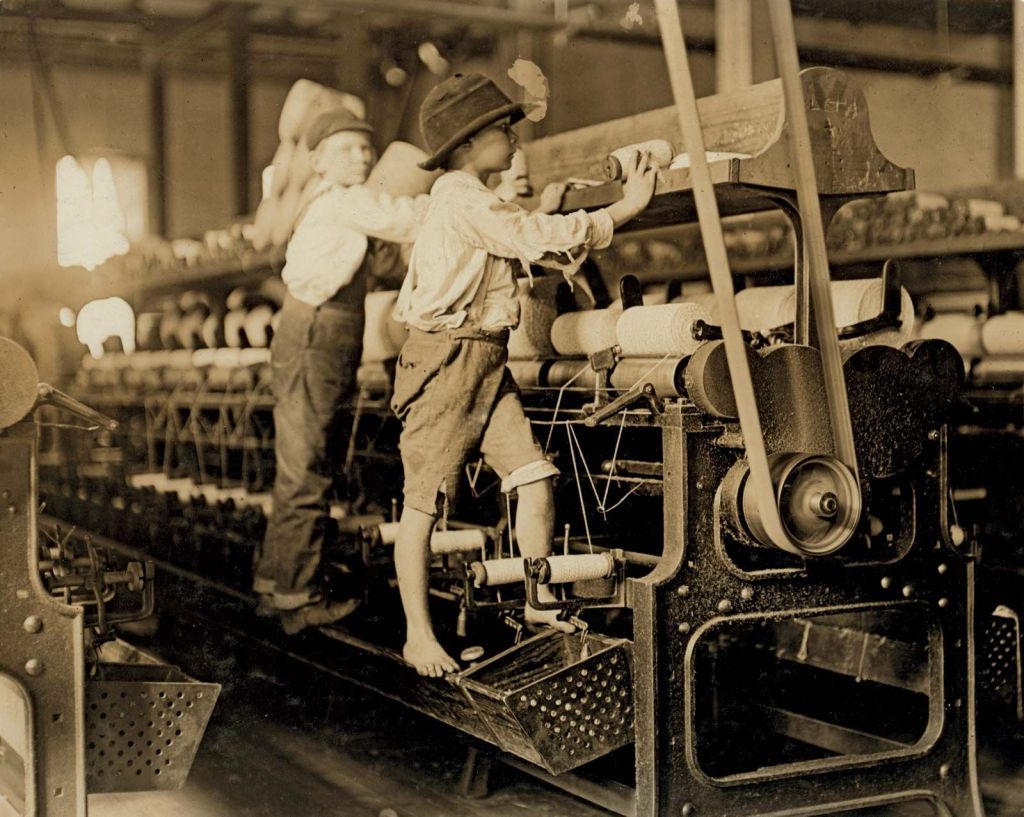

Girls at Weaving Machines, Evansville, IN

Click to Enlarge

Girls at Weaving Machines, Evansville, IN

October 1908

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523100

Young Boys Schucking Oysters, Apalachicola, FL

Click to Enlarge

Young Boys Schucking Oysters, Apalachicola, FL

January 25, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523162

Girl Working in Box Factory, Tampa, FL

Click to Enlarge

Girl Working in Box Factory, Tampa, FL

January 28, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523166

Nine-Year Old Newsgirl, Hartford, CT

Click to Enlarge

Nine-Year Old Newsgirl, Hartford, CT

March 6, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523174

Boy Picking Berries, Near Baltimore, MD

Click to Enlarge

Boy Picking Berries, Near Baltimore, MD

June 8, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523205

Workers Stringing Beans, Baltimore, MD

Click to Enlarge

Workers Stringing Beans, Baltimore, MD

June 7, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523215

Boys Working in an Arcade Bowling Alley, Trenton, NJ

Click to Enlarge

Boys Working in an Arcade Bowling Alley, Trenton, NJ

December 20, 1909

National Archives and Records Administration

Records of the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau

Record Group 102

National Archives Identifier: 523246

Detail of Boy Picking Berries

Lesson Resources

The Documents

Standards Correlations

Teaching Activities

Document Analysis Worksheet

OurDocuments.Gov

This page was last reviewed on February 21, 2017.

Contact us with questions or comments.

Teachers’ Resources

Primary Sources

DocsTeach

Visits & Workshops

Other Resources

Connect With Us

Facebook X Instagram Tumblr YouTube Blogs Flickr

Contact Us · Accessibility · Privacy Policy · Freedom of Information Act · No FEAR Act · USA.gov

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

1-86-NARA-NARA or 1-866-272-6272

Skip to Content

U.S. flag

An official website of the United States governmentHere is how you know

Department of Labor Logo United States Department of Labor

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Menu

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Publications

Monthly Labor Review

Monthly Labor Review logo

Archives For Authors About Subscribe

Search MLR

About the Author

Michael Schuman

mschuman79@gmail.com

Michael Schuman was formerly a supervisory contract specialist in the Office of Administration, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Related Content

Related Articles

History of child labor in the United States—part 2: the reform movement, Monthly Labor Review, January 2017.

The life of American workers in 1915, Monthly Labor Review, February 2016.

Labor law highlights, 1915–2015, Monthly Labor Review, October 2015.

Occupational changes during the 20th century, Monthly Labor Review, March 2006.

Compensation from before World War I through the Great Depression, Monthly Labor Review, January 2003.

Troubled passage: the labor movement and the Fair Labor Standards Act, Monthly Labor Review, December 2000.

Related Subjects

Agriculture

Coal

Earnings and wages

Family issues

History

Hours of work

Labor law

Labor law state government

Manufacturing

Working conditions

Youth

Article Citations

Crossref9

top Back to Top

Article

article imageJanuary 2017

History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working

There was a time in this country when young children routinely worked legally. As industry grew in the period following the Civil War, children, often as young as 10 years old but sometimes much younger, labored. They worked not only in industrial settings but also in retail stores, on the streets, on farms, and in home-based industries. This article discusses the use of child labor in the United States, concentrating on the period after the Civil War through the rise of the child labor reform movement.

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.1

—Sarah N. Cleghorn

The September 1906 edition of Cosmopolitan magazine recounts a story once told of an old Native American chieftain. The chieftain was given a tour of the modern city of New York. On this excursion, he saw the soaring heights of the grand skyscrapers and the majesty of the Brooklyn Bridge. He observed the comfortable masses gathered in amusement at the circus and the poor huddled in tenements. Upon the completion of the chieftain’s journey, several Christian men asked him, “What is the most surprising thing you have seen?” The chieftain replied slowly with three words: “little children working.”2

Although the widespread presence of laboring children may have surprised the chieftain at the turn of the 20th century, this sight was common in the United States at the time. From the Industrial Revolution through the 1930s was a period in which children worked in a wide variety of occupations. Now, nearly 110 years after the story of the chieftain was told, the overt presence of widespread child labor in New York or any other American city no longer exists. The move away from engaging children in economically productive labor occurred within the last 100 years. As numerous authors on the subject have remarked, “Children have always worked.”3 In the 18th century, the arrival of a newborn to a rural family was viewed by the parents as a future beneficial laborer and an insurance policy for old age.4 At an age as young as 5, a child was expected to help with farm work and other household chores.5 The agrarian lifestyle common in America required large quantities of hard work, whether it was planting crops, feeding chickens, or mending fences.6 Large families with less work than children would often send children to another household that could employ them as a maid, servant, or plowboy.7 Most families simply could not afford the costs of raising a child from birth to adulthood without some compensating labor.8

One of the authors who noted that “children have always worked” is Walter Trattner.9 During early human history when tribes wandered the land, children participated in the hunting and fishing. When these groups separated into families, children continued to work by caring for livestock and crops. The medieval guild system introduced children to the trades. The subsequent advance of capitalism created new social pressures.10 For example, in 1575, England provided for the use of public money to employ children in order to “accustom them to labor” and “afford a prophylactic against vagabonds and paupers.”11 An Englishman stated, with regret, that “a quarter of the mass of mankind are children, males and females under seven years old, from whom little labor is to be expected.”12 This statement was consistent with the Puritan belief that put work at the center of a moral life.13 This belief shaped a citizenry that grew to praise work and scorn idleness.14 The growth of manufacturing, however, provided the greatest opportunity for society to avoid the perceived problem of the idle child.15 Now that more work was less complex because of the introduction of machines, children had more potential job opportunities. For example, one industrialist in 1790 proposed building textile factories around London to employ children to “prevent the habitual idleness and degeneracy” that were destroying the community.16 With the advances in machinery, not only could society avoid the issue of unproductive children, but also the children themselves could easily create productive output with only their rudimentary skills.

Similarly, in America, productive outlets were sought for children. Colonial laws modeled after British laws sought to prevent children from becoming a burden on society.17 At the age of 13, orphan boys were sent to apprentice in a trade while orphan girls were sent into domestic work.18 Generally, children, except those of Northern merchants and Southern plantation owners, were expected to be prepared for gainful employment.19 In other locations, the primary motivation in employing children was not about preventing their idleness but rather about satisfying commercial interests and the desire to settle the vast American continent.20 Regardless of the motivation, a successful childhood was seen as one that developed the child’s productive capacity.21

As economic tensions increased between England and the American colonies, the desire for an independent manufacturing sector in America became more pronounced. By manufacturers employing women and children in this pursuit, the man of the household could still tend the farm at home. This practice helped fulfill the Jeffersonian ideal of the yeoman farmer.22 Child labor also served the Hamiltonian commercial vision of America, by providing increased labor to support industry.23 In accordance with this vision, Alexander Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, noted in a 1791 report on manufacturing that children “who would otherwise be idle” could become a source of cheap labor.24

Around the same time, the influential Niles’ Register (a national newsweekly magazine) noted that factory work was not for able-bodied men, but rather “better done by little girls from six to twelve years old.”25 Industrialists viewed progress as having machines so simple to operate that a child could do it.”26 This labor was perceived as beneficial not only to the child but also to the public as a whole. In keeping with this ideal of child productivity, an 1802 advertisement in the Baltimore Federal Gazette sought children from the ages of 8 to 12 to work in a cotton mill. The ad stated, “It is hoped that those citizens having a knowledge of families, having children destitute of employment, will do an act of public benefit by directing them to the institution [cotton mill].”27 In New England, the allure of employing children in the mills was thought by one editorial writer to be so strong that it led parents to choose its settlements versus the less developed Western frontier where no such job opportunities existed.28 By 1820, children made up more than 40 percent of the mill employees in at least three New England states.29 That same year, Niles’ Register calculated that if a mill were to employ 200 children from the age of 7 to 16 “that [previously] produced nothing towards their [own] maintenance . . . it would make an immediate difference of $13,500 a year to the value produced in the town!”30

Young girl working at spooling room in the Brazos Valley Cotton Mill, West, Texas, about 1913.

Although the economic value of work for children was emphasized, its perceived underlying benefit was also important in its growth in the 19th century. This value was seen in the nature of the outreach that some organizations such as the Charles Loring Brace Children’s Aid Society (CAS) provided to orphaned children. In establishing its first lodging house for boys in 1854, the CAS emphasized that it would “treat the lads as independent little dealers and give them nothing without payment.” Through avoiding the prospect of idle children, CAS thought it was avoiding “the growth of a future dependent class.”31 It believed that the best way to bring children out of poverty was to have them work at an “honest trade.” To do this, the CAS taught children work skills such as the trade of shoemaking.32 Finding that New York City did not have enough “honest jobs,” the CAS established trains to move orphaned children out West.33 This movement was seen as balancing the supply of youth in the cities with the demands found in rural areas.34 The CAS received further support from abolitionist forces that saw this “free labor” of children as a donation to the cause of “freedom” in the fight against slave labor in the West.35 The success of these children was judged by how much they worked for the Western families that took them in. In annual reports, the CAS published letters that highlighted the productive capacity of the children. These letters reported things such as how the child “does nearly as much as a man” or was earning his keep.36

The parallel beliefs that labor benefited children by helping them avoid the sin of idleness and economically benefited society by helping it increase its productive capacity fueled the spread of the practice. Women and children dominated pre-Civil War manufacturing; however, the low volume of manufacturing caused the number of children employed to remain at low levels.37 The advances in manufacturing techniques in the post-Civil War years increased opportunities for children and led society to take advantage of this productive capacity. Similarly, some of the productive capacity that had been met by the use of slaves was met by women and children in the years following emancipation.

However, in the period immediately following the Civil War, “free labor” was not always clear when recently freed slave children and some immigrant youths were considered. In many cases, former slave children were functionally reenslaved through apprentice agreements, which bound the child to the former slave master. In these agreements, the parent exchanged the labor of the child in return for “training” provided by the former slaveowner.38 These agreements were frequently seen by courts as beneficial to the child because the slave master was in a better position to teach the child “the habits of industry” than were the recently freed parents.39 Although these situations were eventually remedied in the South during the Reconstruction period, similar abuses of the apprentice system occurred elsewhere. In New York City, in the 1870s, the operation of Italian “padrones” (persons who secured employment especially for Italian immigrants) bordered on child slavery under the guise of apprenticeship. The padrones often deceived Italian children and parents (those residing in Italy) into apprentice arrangements, purportedly for teaching the child how to play a musical instrument. Once agreements were signed, the children were swept off to America where they were forced to become street performers with all of their earnings provided to the padrone. Children who failed to comply with the demands of their padrone master were frequently beaten.40 As the New York Times put it in 1873, “The world has given up on stealing men from the African coast, only to kidnap children from Italy.”41

Although the situations involving former slaves and the Italian padrones were egregious, they were a small percentage of the overall number of working children. As child labor expanded through the end of the 19th century, these practices diminished. The 1870 census found that 1 out of every 8 children was employed.42 This rate increased to more than 1 in 5 children by 1900.43 Between 1890 and 1910, no less than 18 percent of all children ages 10‒15 worked.44 Age was only one consideration in deciding whether a child was ready for work. Being “big enough to work” was usually not a metaphor about reaching a certain birthday; rather it was often about the physical size of the child as well as the acumen the child appeared to have in performing the labor required.45 Age and size, however, were not the only factors that determined whether a child worked. Distinctions between children expected to work and those not expected to work made on the basis of family income became increasingly evident. Children from families at the lower end of the class spectrum were frequently employed, whereas the concern about idle youths did not appear to be one shared by the upper classes. As one well-to-do father explained in 1904, “We work for our children, plan for them, spend money on them, buy life insurance for their protection, and some of us even save money for them.”46 At the lower end of the income scale though, families were forced to use their children for their labor without the luxury of saving for their futures.

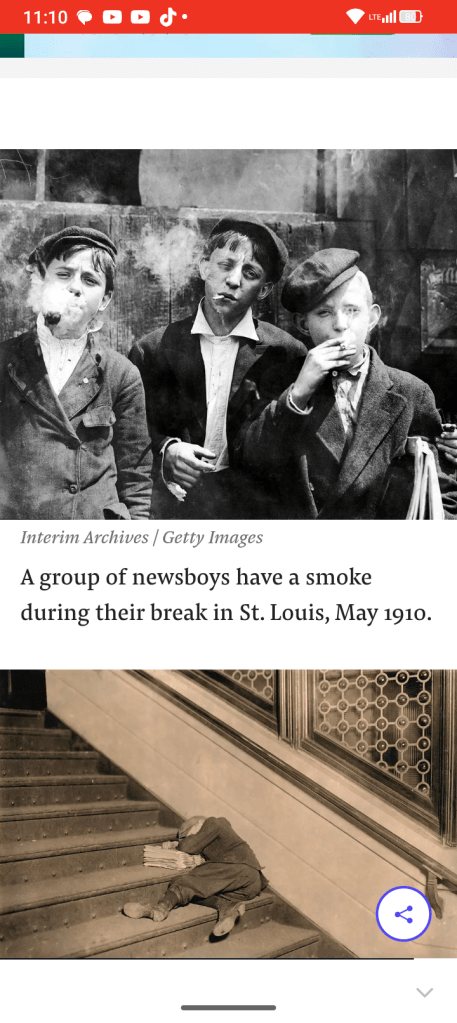

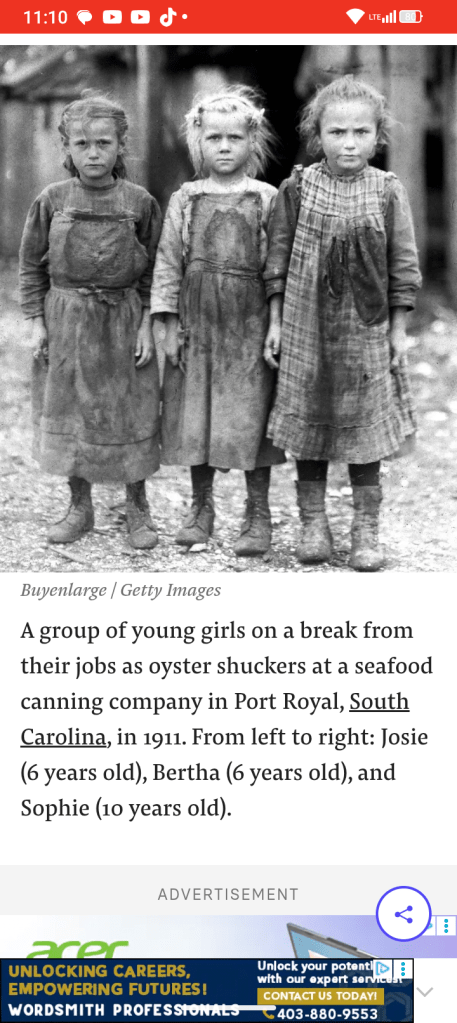

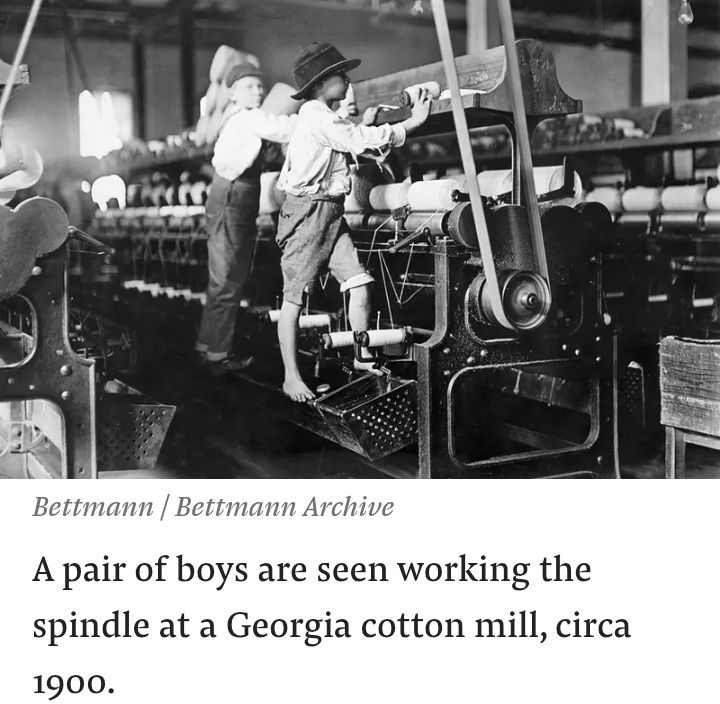

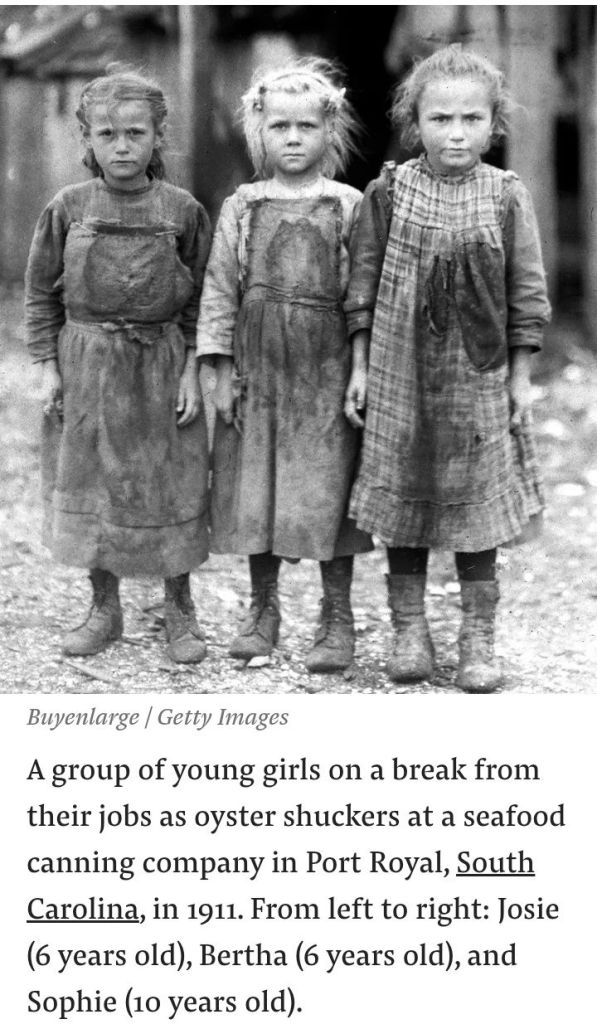

By the turn of the 20th century, the labors that the children of the working class performed were varied. In rural areas, young boys, some reportedly under age 14,47 toiled in mines, sometimes working their fingers literally to the bone, breaking up coal.48 Young lads in urban areas often earned their living as newspaper carriers or as couriers. In many towns, mills and glass factories regularly employed girls and boys.49 Young children worked in the fields performing farm labor and on the coasts in the seafood industry. Even youngsters who never left the house had employment options. Home-based businesses provided children a chance to labor by assembling flowers or other items.50 With so many avenues available for employment, children were seen as a resource, rather than a drain, to many parents who were struggling financially.51

At the turn of the 20th century, children were working in various industries. The discussion that follows highlights some of the occupations in which children labored and examines the employment conditions children faced in detail.

Street trades

As the story of the chieftain illustrates, working children were a widespread presence in urban areas because of the number of occupations they performed. Most visibly, many engaged in occupations working on city streets.52 These children sold newspapers, shined shoes, and carried messages. In the days before the Internet, texting, and even the telephone, these messengers provided the easiest way for people within an urban area to communicate. In this role, they became essential to daily commerce for banks, factories, and offices. At night, they provided these same essential services to brothels and those enterprises conducting other unlawful activities.53 Similar, less tawdry courier services were provided within department stores. Children known as “cash” boys and girls carried money, sales slips, and items purchased to store inspectors. The inspectors wrapped the goods and verified the amounts paid. The children then returned the change and the items.54

Young newsies (boys) at the newspaper office after school in Buffalo, New York, in 1910.

While courier boys were common, newspaper boys, popularly known as “newsies,” worked in the most visible of the street trades and were the face of child labor for most urban Americans.55 According to author Hugh Hindman, saying that most urban kids worked as a newsboy for at least a short period is no exaggeration.56 After buying their papers from the publisher, the newsies would hawk papers on street corners. This arrangement meant that the carriers only profited when they sold a paper. This situation led to fierce competition between the carriers for the best locations. On big news days, a flashy headline helped drive sales of papers; however, on other days, the newsboys needed to use more nefarious means to profit from sales.57 These techniques included shouting out false headlines and shortchanging customers, particularly during the late-night hours.58 During World War I, the shouting of false headlines was such a nuisance that Cleveland, Ohio, threatened to prosecute boys who shouted “false and amazing” statements. In New York City, an October 1917 New York Times article outlined the efforts of police to stop carriers from shouting baseless headlines of war calamities to spur sales.59 Yet, the same article noted that when these enterprising youngsters were hauled before the judge, the police officers were likely lectured for not devoting their time to more serious crimes.60

The newsies also frequently took advantage of the kindness of strangers through their use of the “last-paper ploy.” In such a ploy, the youngster feigned cold, exhaustion, or hunger saying that he or she could go home only by selling the last paper. Once a sympathetic purchaser left with the paper, the newsie pulled out another paper from a hidden stash and used the ploy again.61 Despite devious schemes like these, among themselves, the newsies generally developed a cohesive culture. Rather than picking on the youngest carriers, the older and larger lads frequently looked out for their younger competitors.62

Mines

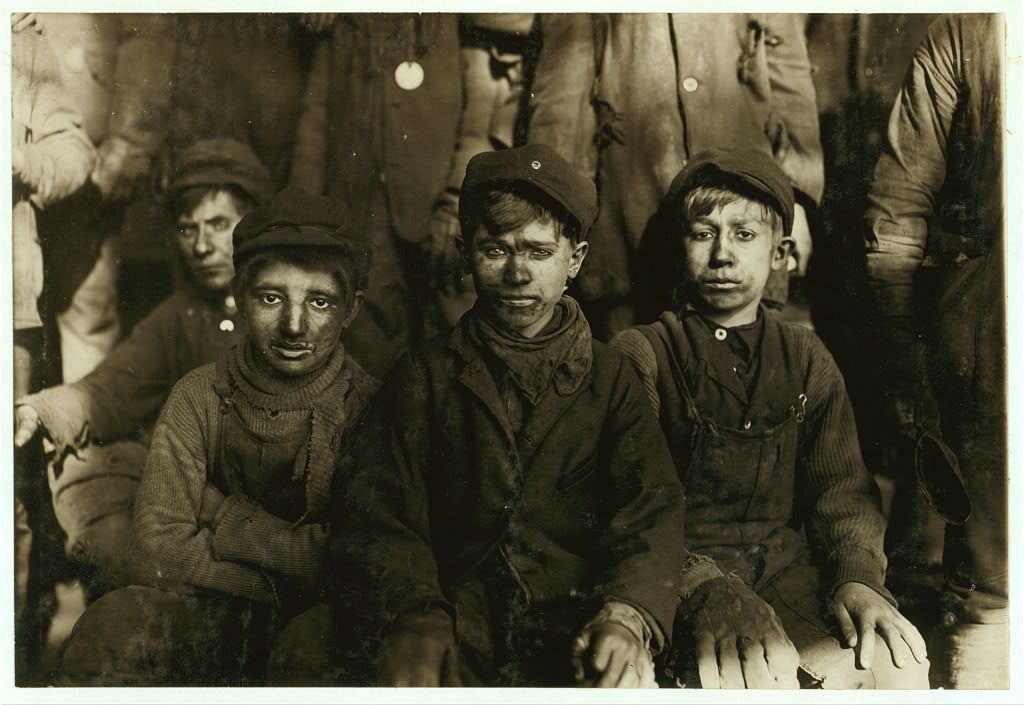

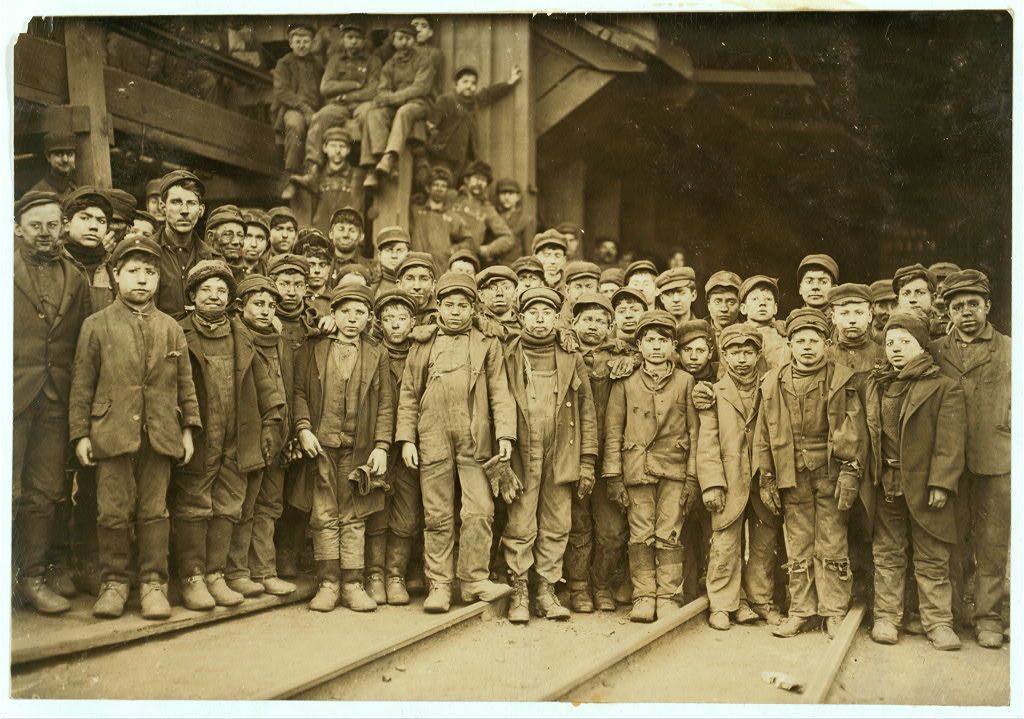

Boy sitting at mine entrance waiting to open door for coal car.Several young boys working in coal mine in early 1930s amongst dust so thick that it obscured their vision.

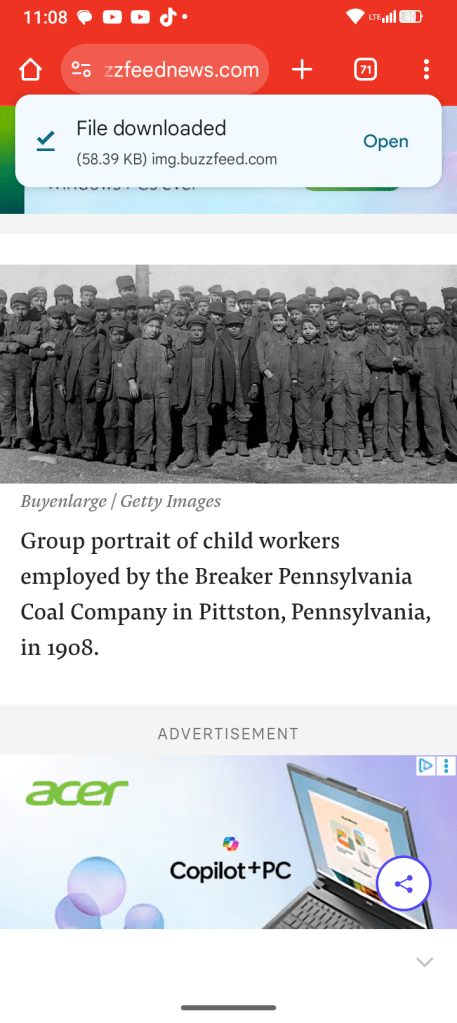

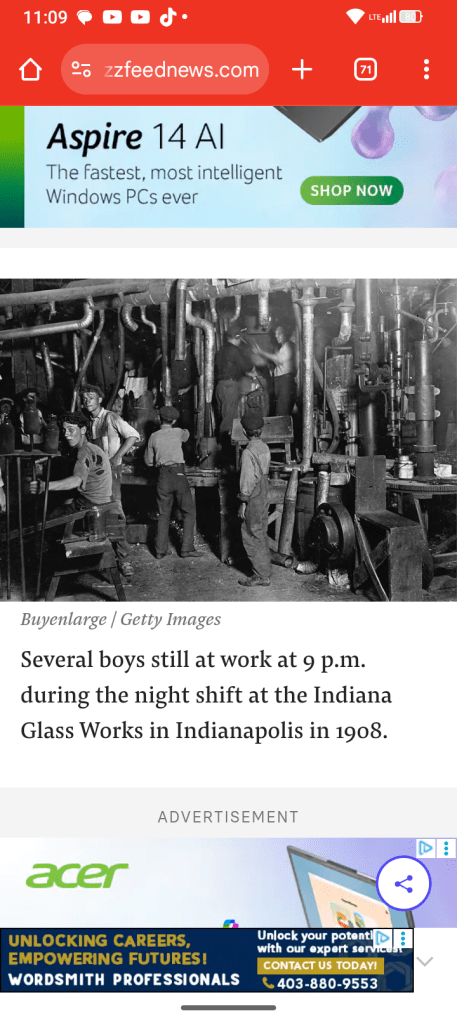

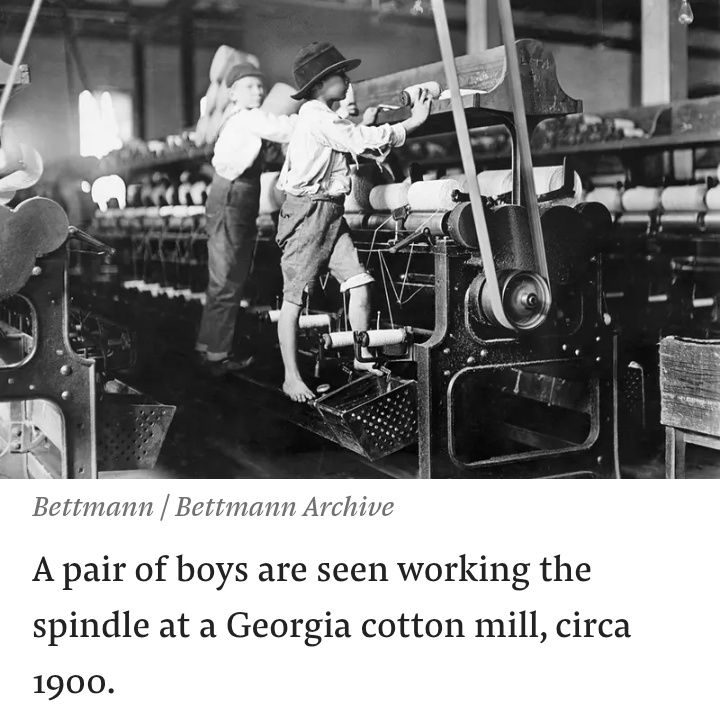

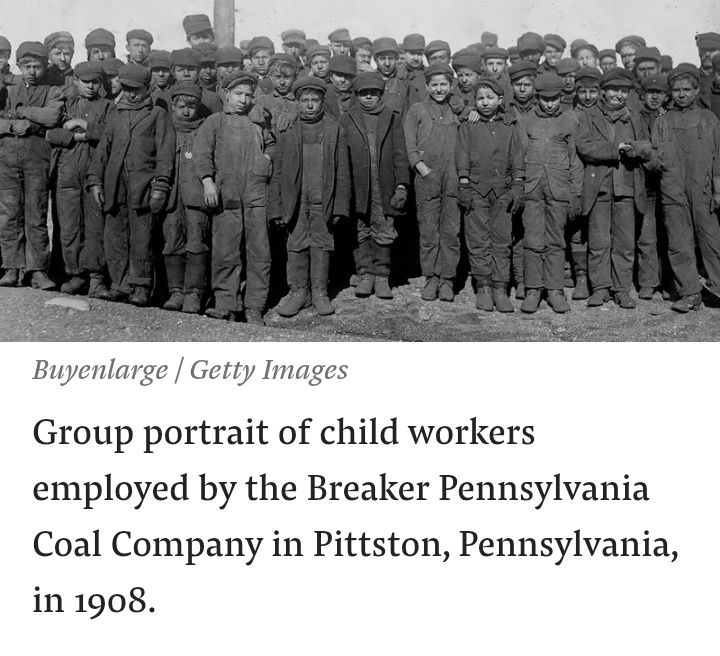

Although many child laborers, such as the newsies, worked in plain view of others on city streets, many did not. While their coal-stained faces have now become known through pictures, at the time, the children who worked in mines labored in relative obscurity. Some labored in the mines as “trappers,” others were known as “breaker boys,” and many worked as “helpers.” The trapper’s sole job was to sit all day waiting to open a wooden door to allow the passage of coal cars. These doors, which were part of the mine’s ventilation system, required opening between 12 and 50 times a day. During the rest of the time, the boy sat in dark idleness next to the door.63 Although less monotonous, the job of the breaker boys was likely more dangerous. Their job was to use a coal breaker to separate slate and other impurities from coal before it was shipped. To do so, these boys, some as young as 14, were precariously position on wooden benches above a conveyor belt so they could remove the impurities as the coal rushed by.64 At times, the dust from the passing coal was so dense that the view would become obscured.65 Other child coal laborers worked as helpers. Journeymen miners frequently hired their own helpers, and some parents hired their own children to perform this role. These children were not usually employees of the mine but were instead paid out of the wages of the journeymen.66

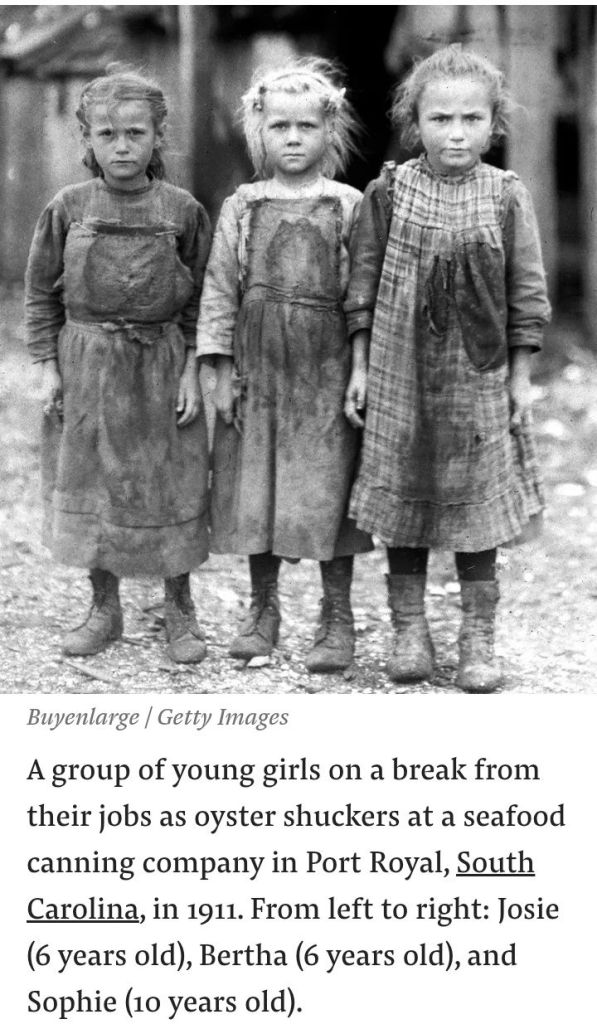

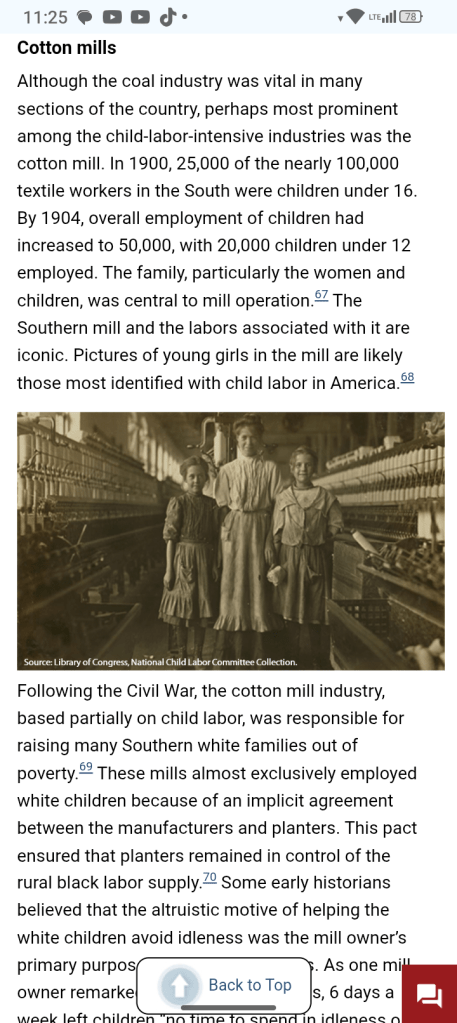

Cotton mills

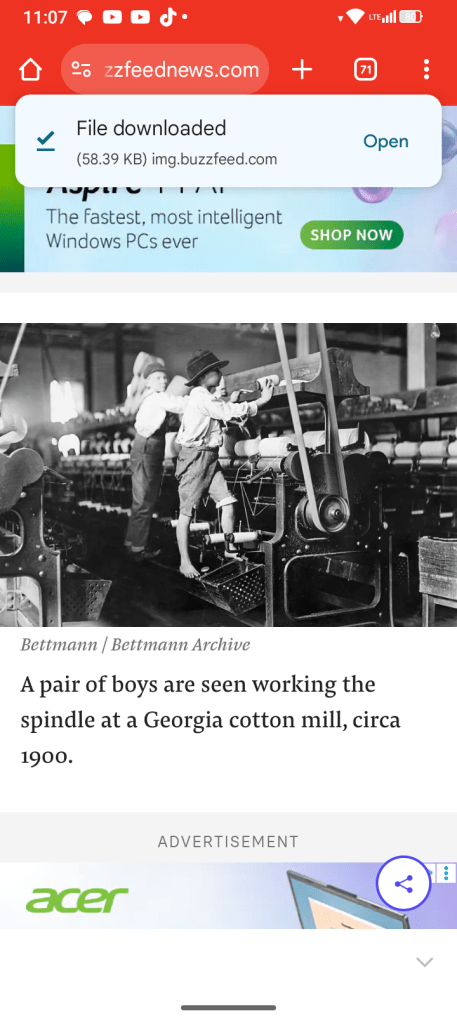

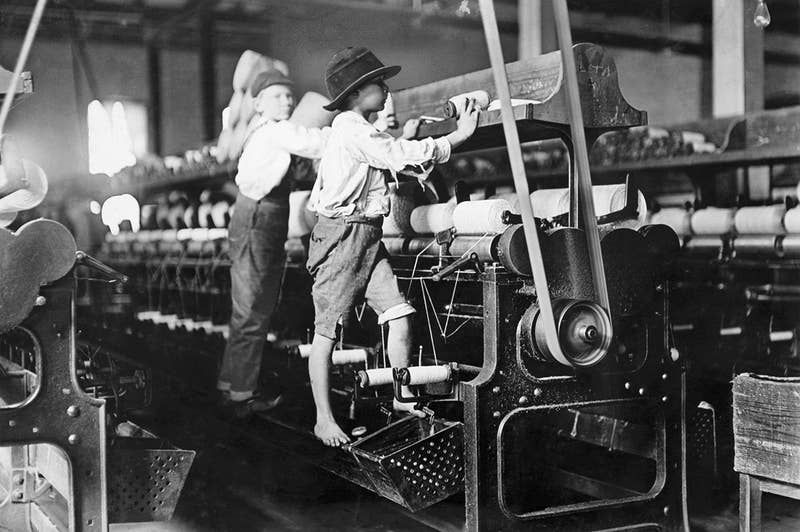

Although the coal industry was vital in many sections of the country, perhaps most prominent among the child-labor-intensive industries was the cotton mill. In 1900, 25,000 of the nearly 100,000 textile workers in the South were children under 16. By 1904, overall eminterest of the mill owner because the children could familiarize themselves with their future workplace.82 At recess during the school day, other children helped by bringing their parents and older siblings meals.83 In many cases, these same children soon made their way to the mill working full time. Usually the boys started as doffers and sweepers while the girls were spinners.84 Doffers replaced the full bobbins filled by spinners with empty ones and often had hours of free time in between their required tasks at the mill.85 These tasks were usually seen as children’s work, whereas other heavier work, such as oiling machinery, was seen as “men’s work.” In the mill, as in most other factory industrial settings at the time, work appropriate for children was clearly differentiated from work seen as appropriate for adults.86 Although mill supervisors oversaw the children who performed these child-appropriate tasks, they were often reluctant to discipline the children. In many ways, the mill was seen as an extension of the family unit. Therefore, for any trouble that the children caused at work, mill owners usually left their discipline up to the parents.87 This approach illustrates just how closely the mill was integrated into the family structure.

Fractories

oysters shucked.103 Children in farming were seldom paid directly for their labor. Their wages were included in the amount paid to the family.104 This system made the head of the household responsible for oversight of all the laborers in the family and allowed the padrone only to deal with a minimum number of subcontractors.105 Under such an arrangement, a child, therefore, was an integral part of the productive capacity of the household.

in the United States. However, reformers faced a long, uphill battle against employers, parents, and the legal system in securing nationwide reform. The legal system, primarily the Constitution and the limited scope of powers it granted to the federal government, proved to be a primary challenge to reform. By the end of the 19th century, the Supreme Court had not heard a single case about child labor. Child labor was a matter for the states to deal with under their own laws, which, in many cases, did not regulate (or barely regulated) child labor. As a result, decades would pass before an observant chieftain would be able to express his surprise at the newfound lack of working children in New York and throughout United States. Part II of this article will detail how the reformers, after decades of struggle, finally succeeded in bringing about this decline in child labor.

Leave a comment